Kildare Town

Its Ancient Roads and Streets

Tadhg Hayden

To the east of Kildare town lies the two thousand hectare spread of the Curragh plain devoid of significant human habitation in early, medieval and modern times. On the north lies a run of small hills – Redmills, Dunmurray Hill, Grangehill, Carrickanearla. To the south-east and south generally are Maddenstown Bog, the King’s Bog and Monavullagh.

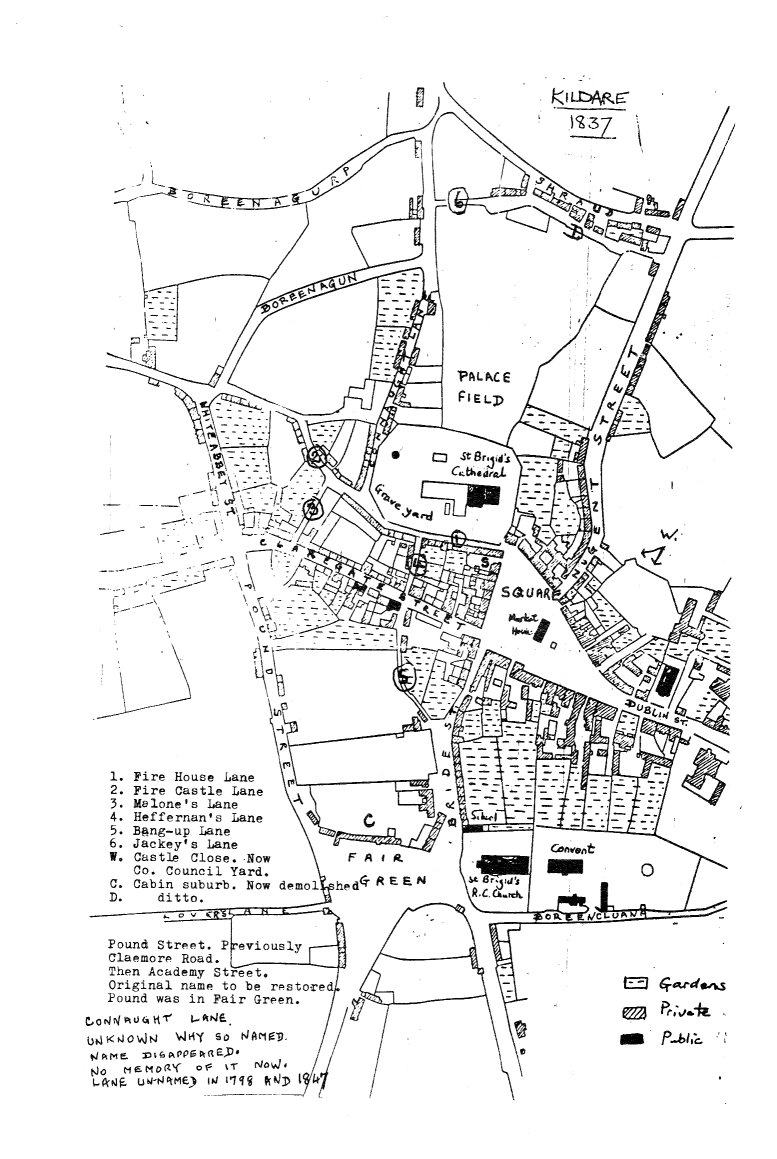

These features fixed the pre-historic approaches to the town. An unexpectedly large number of roads -12 in all – converge on Kildare: two from the north-east, three from the south-east, three from the south-west and four from the north-west. The present main road through the town was a late comer in importance. It began to develop after the Plantation of Laois by Queen Mary and the over throw of the Laois clansmen – the O’Moores, O’Dempseys, Phelans etc. Up to this time the strong Earl’s castle in Kildare° with its four towers and curtain wall and the walls of Kildare town had proved ineffectual in maintaining Kildare as a frontier town on the edge of the English Pale. They were left in ruins. Kildare was replaced by Portlaoise (Maryboro’) after the plantation – and the present route through Kildare down into Munster was opened. The route through Kildare assumed some commercial importance in 1731 when the road from Naas to Portlaoise was turnpiked. An Inn to cater for travellers was opened in c. 1757 in Bang-up Lane near its juncture with Claregate Street. It was near the site Eilis of Heffernan’s garden shop and was called the Kildare Arms Inn

Where approach roads entered the seventeenth century town the description ‘lane’, not road, was widely used e.g. Rathangan laine, Rahillylaine, Lackagh laine, Abbielaine, etc. This usage though disappearing, survived into the eighteenth century. Rocque’s map of 1757 names the present Melitta Road as the Great Lane, recalling a time when this road was a more important route than the present main road through the town. And later still Nugent Street (gradually called Station Road after the opening of the Railway station) was described as Nugent’s Lane in 1767 in the Minutes of the Infirmary Committee when a temporary Infirmary was opened (at the S.E. corner of Nugent’s Lane’. The permanent Infirmary (now Derby House Hotel) was opened some distance away in 1777.

The lane by the cathedral wall at Fitzpatrick’s butcher’s shop is Fire House Lane. This ancient name survived on the lips of older residents. Fire House Lane forks after a short distance. The fork leading towards the parochial house is Fire Castle Lane. This name had fallen into complete disuse and survived only on old maps. No significant traces of the castle in question remain. Both names – in Irish and in English – are now preserved for posterity on wall nameplates at the entrances to these lanes

The fire referred to in these names is St. Brigid’s Fire. It was kept perpetually alight here by St. Brigid and her successors. It was finally extinguished when the convent (at the back of the present cathedral) was confiscated and demolished by Henry VIII. But this perpetual fire pre-dated St. Brigid. She took it over (and christianised it) from the pagan priestesses who met periodically in the oak grove on this spot, praying for good crops and stock, invoking the goddess Brigid (same name as the saint). The oak was the sacred pagan tree. It is perpetuated in the name of the town – Cill Dara – the church of the oak. Imbolg (the beginning of spring) was an important pagan festivity here. This date is also the feast day of Brigid the saint. Brigid the goddess and Brigid the saint bear the same name. And the sacred fire was kept alight in pagan and Christian times until Archbishop Browne finally extinguished it in the sixteenth century

Two name-plates attached to two walls at the entrances to two lanes now proclaim the mind-boggling antiquity of Kildare’s links with the remote past in Ireland and abroad. Preserved memories of the cults of the oak, the fire and the well (St. Brigid’s well, Tully) indicate a pagan and then Christian pedigree stretching backwards through thousands of years to our remote ancestors in Ireland and beyond them over thousands of miles to their original homeland in eastern Europe beyond the Danube where they observed the same religious practices. And there is an indirect link with ancient Persia (Iran) and modern India. In prehistorical times the ancestors of the Iranians moved into Persia (Iran) from the shores of the Caspian. They observed the cult of the perpetual fire – as it was observed in Kildare. This would appear to indicate a theological link with the Celts. And a migration of Persians into India took place in the remote past. From their homeland, Airyana-vaejo, (the Aryan Home – Iran) they brought into India the cult of the perpetual fire. Today in India the Parsees, their descendants, practise the cult of the fire in their temples which are empty edifices with the exception of a fire in a fireplace in the centre of the building – a fire kept perpetually alight as such a fire was kept permanently burning in Kildare

An absence of early maps of Kildare make it difficult morphologically to establish with any real certainty the original lay-out and importance of streets in the early medieval town and the extent to which the square was gradually widened. An account of Kildare after the wars of Elizabeth 1 records that Kildare was ‘totally disinhabited’. Kildare had a long history of attack and the inevitable destruction of buildings. In post-Norman times the square may safely be assumed to have gradually widened to its present size. Some streets – Claregate Street and Dublin Street – would have developed and grown in importance after the establishment of the Earl Marshall’s castle, gradually pivoting away from the cathedral at their confluence. And streets running at right angles to them would have narrowed and shrunken in importance. One of the latter could have been Sraid Gaterelylaure (Geata Roilig Lair). On the meagre evidence available this lost street could have been the ancestor of Malone’s Lane. An unidentified street is Sraite in cheim chloiche. The evidence contained in the name (the street of the stone steps) means that this street could have been any one of the several steep lanes leading towards the cathedral. Eighteenth and nineteenth century maps of Kildare show an unexpected amount of demolition and rebuilding as well as encroachment on open spaces in some cases and the creating of open spaces in others. Radical demolition continued into our own time. In recent years a line of houses forming two thirds of south Claregate Street was totally demolished to widen the road. And cabin-suburbs once forming compact units are all gone

Streets in Kildare had no name-plates in position to identify them. In 1985 some steps were taken to remedy this omission. Bilingual name-plates now label the following: Claregate Street, Bride Street, White Abbey Road, Nugent Street, Boreenacloona (Meadow Road), Borreenagurp, Fire House Lane, Fire Castle Lane, Heffernan’s Lane, Malone’s Lane, Dublin Street

The Irish version of Claregate Street now explains the name – Sraid Gheata an Chleir – the Street of the Gate of the Clergy. An ancestor of this street led to a gate used by clergy when entering the more extensive complex which stood where now the cathedral stands. Bride Street for a period was called Bergin Street. A prominent local family of this name lived where the de la Salle property is located. The building of St. Brigid’s Catholic church in 1833 (tower added 1851) at the end of this street led to the restoration of the original name. The Carmelites were known as White Friars. After emancipation they returned to their original site from which they had been expelled by Henry VIII. The name White Abbey Road had dropped into general disuse. It happily has been restored. The railway station (Great Southern and Western Railway) was built in 1847 at the end of Nugent Street. Over the years the description Railway Road gradually replaced Nugent Street in general usage. When the street name-plate was put in position on this street it was felt that the term Railway Road had acquired connotations which could not be ignored. By way of compromise Railway Road was put on the plate with Nugent Street in brackets beneath it. This meant that there was no room for an Irish version of either name! Boreenacloona – this road ran by the Convent. To a certain extent the term Convent Road tended to replace the historic name. The name-plate here now restores the original name written Bothar na Cluaine with Meadow Road as a translation. The Heffernan family referred to in Heffernan’s Lane still live in Claregate Street. Hennesseys of Claregate Street are related to the Malone who gave the name to Malone’s Lane. The road between the back of the Vocational School and the Park is Borreenagurp – Bothairin na gCorp – the Road of the Corpses! The location of this road was firmly fixed by older residents. There was some confusion since one map put this road on the south side of the Vocational School, confusing it with Boreenagun – Bothairin nag Con. In the case of Bothairin nag Corp the Irish version only – for obvious reasons – was put on the street name-plate

Streets yet to be labelled: Academy Street (Claemore Street), Bang-up Lane, Hospital Street, Blindwell Lane, Cross Keys, Chaplin’s Lane or Cox’s Lane, Jackey’s Lane, Pigeon Lane, and if possible, Lovers Lane

The de la Salle Brothers opened a secondary school called the Academy in Claemore Street in 1884. Down the years the name  Academy Street tended to replace the old name Claemore Street. The old name will be restored on a street name-plate. Claemore is Claidhe Mor – Big Ditch. Though the name has defensive military implications this Ditch was not part of the town walls. Hospital Street is not as one might reasonably assume named after the Infirmary to which it led. It refers to Lock’s Hospital which was. built by the British military on the site of the present Artillery Barracks. It was for treatment of venereal disease. It was closed in 1887 having been built in 1868. Blindwell Lane leads to wells called the Blind Wells. The name Blind Well is comprehensible when translated back into Irish – Tobar Caoch i.e. a well that periodically runs dry. The garrison of the Earl Marshall’s castle (built c. 1200) must have depended on these wells in the main for domestic water. One can sympathise with the Quartermaster. He must have had problems – though the persistent assaults of the O’Moores proved the final problem! Incidentally the building now called The Castle is in fact a Tower House of a much later period. And the circular tower on the perimeter wall of Beech Grove House is a Folly probably added when the house was remodelled c. 1810. All these are on the site of the Earl’s castle and stones from the demolished castle were apparently used to build them. Cross Keys is Cros Chae – St. Cae’s way-side cross – long since demolished. Cae was apparently a local saint. His church was at Kilkea (Cill Cae) between Castledermot and Athy. Older residents in Kilkea still pronounce the name correctly i.e. Killkay. Lovers Lane was closed at the beginning of the present century. It was between Mr. Watter’s house and the Presentation Girls’ Primary School. It led to a well called the sovereign’s well. It has been suggested that ‘Lover’ is a corruption of ‘Lobhar’, a leper or anyone with skin disease. This`implies a hospital. There is a reference to an unidentified medieval ‘maudlins’ somewhere on the outskirts of Kildare. Perhaps Lovers Lane led to this hospital?

Academy Street tended to replace the old name Claemore Street. The old name will be restored on a street name-plate. Claemore is Claidhe Mor – Big Ditch. Though the name has defensive military implications this Ditch was not part of the town walls. Hospital Street is not as one might reasonably assume named after the Infirmary to which it led. It refers to Lock’s Hospital which was. built by the British military on the site of the present Artillery Barracks. It was for treatment of venereal disease. It was closed in 1887 having been built in 1868. Blindwell Lane leads to wells called the Blind Wells. The name Blind Well is comprehensible when translated back into Irish – Tobar Caoch i.e. a well that periodically runs dry. The garrison of the Earl Marshall’s castle (built c. 1200) must have depended on these wells in the main for domestic water. One can sympathise with the Quartermaster. He must have had problems – though the persistent assaults of the O’Moores proved the final problem! Incidentally the building now called The Castle is in fact a Tower House of a much later period. And the circular tower on the perimeter wall of Beech Grove House is a Folly probably added when the house was remodelled c. 1810. All these are on the site of the Earl’s castle and stones from the demolished castle were apparently used to build them. Cross Keys is Cros Chae – St. Cae’s way-side cross – long since demolished. Cae was apparently a local saint. His church was at Kilkea (Cill Cae) between Castledermot and Athy. Older residents in Kilkea still pronounce the name correctly i.e. Killkay. Lovers Lane was closed at the beginning of the present century. It was between Mr. Watter’s house and the Presentation Girls’ Primary School. It led to a well called the sovereign’s well. It has been suggested that ‘Lover’ is a corruption of ‘Lobhar’, a leper or anyone with skin disease. This`implies a hospital. There is a reference to an unidentified medieval ‘maudlins’ somewhere on the outskirts of Kildare. Perhaps Lovers Lane led to this hospital?